Native + Invasive Plants

This is a regular topic of conversation in the Parks & Natural Resources division. Native plant nurturing vs. managing the removal of invasive plants. So, what’s the big deal? Native plants are those indigenous to a particular area and invasive plants are not–they were transported here through some means and they establish and proliferate, displacing native plants, and causing harm to the environment, public health, or the economy. Invasive plants often establish with a quick rate of spread that outcompetes native plants for resources such as water, sunlight, and soil nutrients. This rapid spread causes a significant decline in the natural cycle of regeneration of native plant communities that rely on a more methodical approach which benefits the lifecycles of other organisms that share the ecosystem around them, such as decomposer communities of fungi, insects, and invertebrates. We encourage you to visit some of our community partners’ websites to learn more on the topic of native vs. invasive species.

Native Plants

According to the Indiana Native Plant Society, “a native plant species is one that has occurred naturally in an area for a very long time. More specifically for Indiana, a native plant species is one that occurred in natural communities—natural plant associations and habitats—within the state boundaries prior to European contact.”

Native plants play an essential role in the ecosystem and they are what form plant families and communities that turn into habitats.

Native Indiana Trees

PawPaw

The Indiana banana! This species, although native to eastern and central US, is a tropical looking fruit. It grows in many of our low woodlands, like Central Park East woods! The pawpaw has been used for generations for various purposes. The bark was used for making fabric as well as a medicinal extract, and the fruit was is used for puddings or eating raw. The taste of the pawpaw is tropical, similar to a banana or mango. The pawpaw fruits grow in clusters and are greenish yellow, turning greenish-brown when ripe. Animals also love pawpaw fruit, so it can sometimes be a challenge getting to the fruits before other critters.

Maple

These trees are common across the Midwest often known for their brilliant red, yellow, and orange colors in the fall. There are several different species of maple found across our state and within our parks. The genus, Acer, is Latin for “sharp,” referring to the sharp-looking pointed tips on maple trees. Sugar maple trees have historically been well-loved for the deliciously sweet sap that flows through them during the winter months that can be made into maple syrup.

Tulip Poplar

Indiana’s state tree! The tulip poplar is a fast-growing tree native to the Eastern hardwood forest and found throughout several of our parks. In the Magnolia Family, the tulip has bright yellow-green flowers with an orange center that makes them extra showy. The tulip poplar is also popular for wood furniture since the wood is lightweight and easy to work. The tulip became Indiana’s state tree in 1931. In 1923, the tulip’s flower became the state flower, however now the state flower is the peony.Benefits of Natives

Native species offer numerous benefits including food for wildlife, habitat, pollination, biodiversity, sustainability, and clean water. Research shows that native plants support far more species of butterflies and moths than non-native plants. The data below, from University of Delaware researcher Doug Tallamy (author of Bringing Nature Home), shows the correlation between native woody species and the number of butterflies/moths it supports. Many birds are insectivorous, meaning they primarily feed on insects, and native plant species support the highest number of insects. This means the more native plants available as a host, the higher the insect populations and the more food for birds. In short, more native plants = more insects = more birds.

Native species have also coevolved with insects over time, forming symbiotic relationships. Non-native plants that are introduced to an area have not been able to coevolve; therefore, they lack a symbiotic relationship. Non-native plants generally have defensive chemicals in their tissue, killing the native plants around them and warding off native insects. Bottom line, native insects thrive with native plants, and vice versa making this a healthy and balanced relationship in the ecosystem.

It’s important to consider the correlation between native plants and insects when thinking about what you want to plant in your backyard. When considering species to plant, think a) is it a native species to where you live? and b) how many other species of insects and wildlife will benefit from this host plant?

Why CCPR Plants Native

Through years of restoring native plant communities, we recognize native plants play an essential role in our ecosystem. We practice what we preach by planting natives every chance we get and offering nature education programs that offer hands-on experience into the value they bring to our surroundings. Whether we are planting a wooded edge, prairie, or wetland community, we choose plants native to that area. We hope you’ll enjoy recognizing the blossoms of some of your favorites the next time you stroll through the park.

Certain mature CCPR native plant communities have achieved a status of sustainability, thanks to countless hours keeping out invasives, which allows us to harvest limited amounts of native seed and prepare for utilization in other regional native plant restoration projects across the Midwest with our friends at the Pollinator Partnership. In 2021 CCPR was awarded the Clark Ketchum Conservation Award from the Indiana Park and Recreation Association for the participation and accomplishments through this program with the Pollinator Partnership.

Native Plant FAQs

-

Where do I buy native plants?

There are several native plant nurseries to support locally: https://indiananativeplants.org/landscaping/where-to-buy/

-

What is pollination?

Living organisms strive to create their next generation. Pollination is how flowering organisms achieve this reproduction. It happens when pollen from the male part of a flower (stamen) is transferred to the female part of the flower (stigma). Pollination can happen only when pollen is transferred between flowers of the same species by animals and insects or even the wind.

-

Who are pollinators?

Pollinators include bees, flies, birds, butterflies, moths, bats, wasps, and mammals.

-

How do I plant a pollinator garden?

Planting a pollinator garden doesn’t have to be complex. A few things to keep in mind:

- Plant a variety of native species to target various pollinators

- Plant species for all times of the growing season (spring, summer, and fall).

- Plant species that are attractive to your eye. Pollinator plants are beautiful. Find some species that you find appealing for your landscape and incorporate them.

-

How do I plant a rain garden?

Rain gardens can be especially beneficial to areas on your property that capture runoff. The runoff may be from your roof, driveway, or maybe a patio. These gardens absorb the water that would otherwise wash pollutants from your roof, driveway, or patio into the nearest water body. Rain gardens do not have to be deep, they can be a shallow depression less than a foot deep. These gardens won’t always hold water, but their purpose is to slow down the runoff and then water slowly seeps in the ground over time. Depending on the amount of rain in a period, these rain gardens act as a sponge to sift nutrients as well as pollutants.

Invasive Plants

CCPR partners with the Hamilton County Invasive Partnership to combat invasive species and educate our community. In September 2020, a survey was sent out by the Technical Committee to determine what the worst invasive species are in Hamilton County. Knowing this would allow the Hamilton County Invasive Partnership to take the actions necessary to help others in the battle against invasive species. A strike has been formed to take physical action in removing invasives from properties across the county.

Three Common Invasives

Need to replace some of these in your own yard? Visit hcinvasives.org for information on native alternatives.

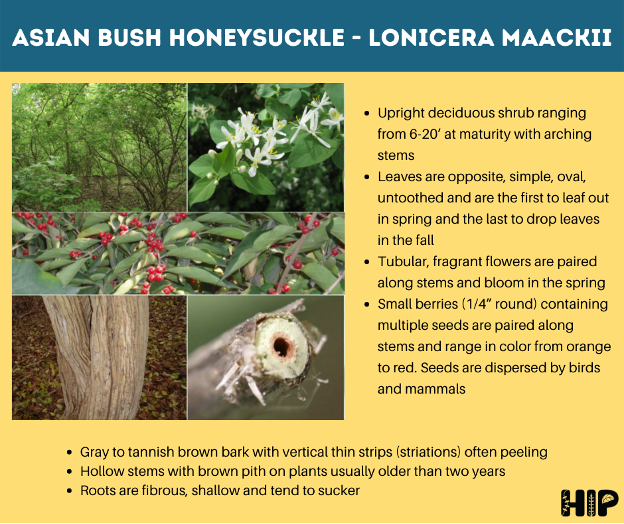

Asian Bush Honeysuckle

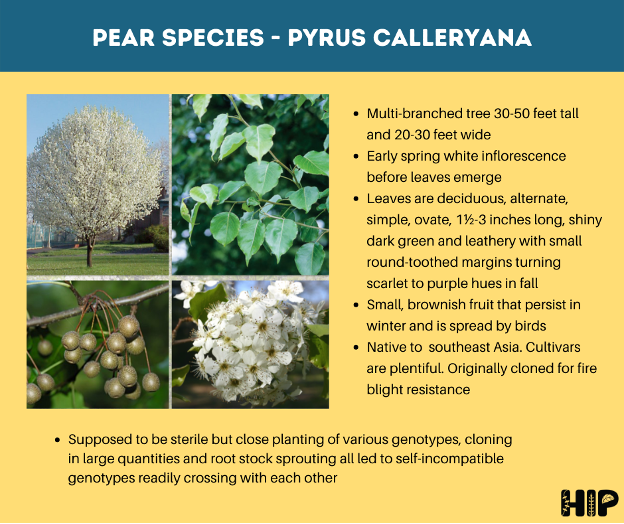

Bradford Pear

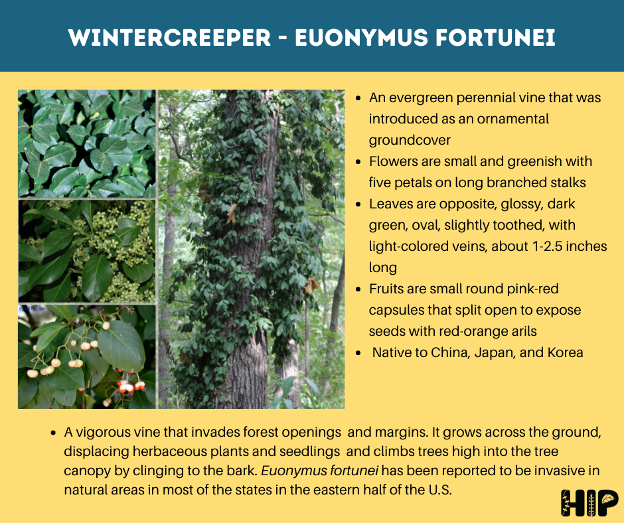

Wintercreeper

How CCPR Handles Invasive Plants

CCPR is actively managing invasive species in our parks and along our greenways to create healthier parks for our community. We prioritize ridding invasives to make room for native species to thrive. Invasives are not only harmful to the ecosystem but they are harmful to the economy as well.

CCPR manages invasive targets strategically, based on the season and the most efficient use of available resources. For example, we use different strategies to remove bush honeysuckle depending on the season and the surrounding environment. Sometimes we can uproot it, sometimes we have to cut it and treat the stump.

CCPR records the expenses that go into invasive species removal. This not only helps manage our own division and parks system, but also aids in the overall quest to educate the community, allow policy makers to realize the impact that invasive species have on the economy, and ultimately create change in our society with legislation or approvals of targeted funding requests.

Invasive Plant FAQs

-

How can I get rid of my invasive plants?

- The best way is to start early! Get after it while the plant community is small or before the individual species is large enough to require more advanced methods. It’s not always an option to get after these targets when they’re small or young though. – Maybe this bullet goes at the end? Maybe not, trying to start the difficult conversation though with a silver lining.

- Be sure you know your target and beyond. Make sure you have done good field identification to verify what you want to remove is actually what you think it is. You also want to make sure any good plants nearby are properly identified and you mitigate the removal impact on anything desirable that you want to keep. Once you have your target identified…

- The next step is figuring out the proper time for management and techniques for removal. What tools or herbicides do you need? Remember, seeds can be dormant in the soil for several years after the plant has been removed, so it will take a constant effort to make certain the species will not return.

- Invasive species removal or mitigation is not always an easy feat. It takes persistence and well-intended effort to gain background. Invasives come in many different forms including small shrubs, bushes, vines, and ground cover.

- Lastly, after removal, it’s important to have a plan for what is going to fill in the space where the invasives once were. You may even want to take extra time to evaluate what grows from seed within the new void you’ve created because you may be surprised, and a dormant native seed may grow up into a strong plant to greet you.

-

How can I help CCPR get rid of invasive plants?

We offer several opportunities for the public to learn more about invasive species with hands-on engagement.

-

- You can help us at one of our workdays throughout the year dedicated to identifying and removing specific invasive targets.

- You can participate in one of our Citizen Science opportunities to monitor the location of invasives in the parks as an Invasive Species Monitor.

- We also partner with local groups, like Hamilton County Invasives Partnership (HIP), for regional coordination and hosting Weed Wrangles to bring awareness to the issues.

- We encourage anyone who has an interest in invasives species challenges to engage with us. We guarantee you will learn something new just by showing up! If you’re not sure where to begin, contact us and we’ll see if we can find a good fit for your interests.

-

-

Comparison of Native vs. Invasive Plants

Research shows that native plants support far more species of butterflies and moths than non-native plants. The data below, from University of Delaware researcher Doug Tallamy (author of Bringing Nature Home), shows the correlation between native woody species and the number of butterflies/moths it supports. Many birds are insectivorous, meaning they primarily feed on insects, and native plant species support the highest number of insects. This means the more native plants available as a host, the higher the insect populations and the more food for birds. In short, more native plants = more insects = more birds.

Native species have also coevolved with insects over time, forming symbiotic relationships. Non-native plants that are introduced to an area have not been able to coevolve; therefore, they lack a symbiotic relationship. Non-native plants generally have defensive chemicals in their tissue, killing of the native plants around them and warding off native insects. Bottom line, native insects thrive with native plants, and vice versa making this a healthy and balanced relationship in the ecosystem.

It’s important to consider the correlation between native plants and insects when thinking about what you want to plant in your back yard. When considering species to plant, think a) is it a native species to where you live? and b) how many other species of insects and wildlife will benefit from this host plant?

-

Indiana Terrestrial Plant Rule

We know invasives are bad, so what are we doing about it?

The Indiana Terrestrial Plant Rule went into effect April 18, 2019. It is a declaration that no one may sell, gift, exchange, distribute, transport, or introduce any of the 44 species within the Indiana Terrestrial Plant Rule. The Department of Natural Resources- Division of Entomology and Plant Pathology (DEPP) is the regulating authority and enforcer of the rule.